Whom Can We Trust?

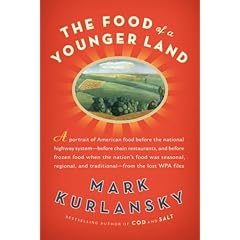

I just finished reading Mark Kurlansky's The Food of a Younger Land. It is terrific book in many ways. It confirms Kurlansky's place as an historian, it serves as a snapshot of a particular time in history, and it calls our attention to an earlier time that involved foodways. We are reminded that we did not just invent the table. In addition the panoramic sweep of the book shows us the entire country, which allows us to see regional trends as well as border influences.

But the book is important to me as I read old cookbooks and read books written by restaurant chefs, the book makes me wonder what can we believe from old cookbooks. Where is the line between story and history? I read a cookbook today with some skepticism - considering the author's agenda and mindful of what may be omitted. But old cookbooks are read as pieces of history. I think that this is probably not wise.

Recently there was a workshop at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study that explored the pitfalls and benefits of relying on cookbooks for historical research. A recent analysis by Rien Fertel of Lafcadio Hearn's book, La Cuisine Creole, revealed plaigarism from other cookbooks and questioned its place in the pantheon of Creole cookbooks. So I am not alone in my questioning.

I know that even when I reveal my warts I want them to be seen in the best light. It is interesting that cookbooks - while appearing to be objective presentations of data - are as biased as a memoir. To me that means that the study of foodways and eating is a fruitful way to learn about the human condition. We wouldn't spin our food stories, if it weren't central to our lives.

5 comments:

I've heard that 'history' as a whole topic is re-written all the time.

Here's an interesting question: If you were placed inbetween a book written by food historians with degrees in various fields who have 'done the right thing' by providing sources and bibliographies for their information on one side - and a live person who is giving an oral history of their own experience which may not match the thrust of the book's narrative, which one would you gather to yourself as 'true'?

Elizabeth, Cookbooks make excellent sources for history. But like all historical documents they need to be used with caution. If you take them as a record of what people ate, then you will probably be misled. If you take them as a record of a culture's values, aspirations, what one author chose to communicate to a given audience at a particular time, then you are safe. And cookbooks usually reveal things not specifically about cooking, but about gender roles, class anxiety, even political agendas. I'm atually writing an essay on this for an Oxford Handbook to fod history right now.

Ken

karen great question,

Having done a great deal of reserach on foodways during my tenner at CIA. I would say you never take anybook as the say all, end all athority on any subject. I find this true with a great deal of book our louisiana culture. Most books are writien from a persons given histroy without much, if any research on the larger picture.

I will say that one persons widow does help paint a the larger picture for the resercher. But need to be balanced with histrocal text as well as adcadmic text.

Just like the lawyer that I am I will give the lawyer waffle for an answer. I would examine the plausability of each of them and decide. I don not believe there is one answer. A diarist who is writing for herself is more believable to me than a person trying to sell cookbooks, even when they are contemporaries.

That Schlesinger Library workshop sounds really interesting. I've found similar issues trying to use old cookbooks in my own research. Plagiarism is one aspect, and social aspirations are another--before deciding how to use the information in a cookbook I think you first have to understand who wrote it, why they were writing, and what their own sources and motivations were. Cookbooks are wonderfully rich sources for historical information, but--as Ken Albala pointed out--you do always have to hold them a little at arms length.

A very thought-provoking post!

Post a Comment